Carthage Blog 10 - Hannibal

- Jul 6, 2025

- 19 min read

Updated: Jul 20, 2025

Who was Hannibal Barca?

Hannibal was a Carthaginian general and statesman in charge of the forces of Carthage in their battle against the Roman Republic in the Second Punic War. The name Hannibal derives from the common Phoenician "Hanno" combined with the Northwest Semitic Canaanite deity Baal, meaning "lord". The combined meaning of the name is something akin to "Ba'al has been gracious".

The track Hannibal is Track 10 on my "Carthage" album. It has not been released yet, but you can listen to it here on my website. I strongly suggest you do!

The Phoenicians, like many other Western Asian Semitic peoples, did not use hereditary surnames, but relied on patronymic names or epithets. Hannibal, when clarification was needed, although he's the most famous Hannibal ever, was referred to as Hannibal, Son of Hamilcar (Barca). Although they do not directly inherit the surname of the father, Hamilcar's progeny were collectively known as Barcids, thus giving Hannibal the name Hannibal The Barcid or Hannibal Barca. The name Barca is a Semitic name meaning "lightning" or "thunderbolt". Barca derives from the ancient Hebrew name "Barak", which in Arabic turns into "Barack". Hmmm. Interesting. I think we know of somebody with that name. Anyway...

The Phoenicians were an early Semitic people. But not in the modern sense. This definition has changed. I don't really want to get into all that here, but there's an interesting post on Wikipedia about the term Semitic people and how it's evolved over the years. I'll leave it there. If you're interested, read the article. I'd like to talk about Hannibal.

Hannibal was the son of another great Carthaginian general, Hamilcar Barca, who led Carthage in the First Punic War against the Roman Republic. His brother and brother-in-law were also Carthaginian war leaders. Hannibal lived in a very difficult time for Carthage triggered by the emergence of the Roman Republic as a major power in the Mediterranean region and the defeat of Carthage in the First Punic War. I'm also learning about the Roman Republic as we go here because the fate of Carthage was unquestionably intertwined with the Roman Republic. We aren't talking about the Roman Empire here, which didn't exist until 27 BC when they switched from being a Republic to being under Imperial Rule . I wasn't aware of that fact.

It is believed that Hannibal was most likely born in Carthage; however, there's no records of this. There were very few records of anything left after Rome destroyed Carthage. After Carthage was defeated in the First Punic War, Hamilcar was inclined to attempt to improve his family's and Carthage's futures. With that in mind, Hamilcar, with the support of Gadir (Track/Blog 6) in Southern Spain, Hamilcar began the subjugation of tribes on the Iberian Peninsula. At that time, Carthage was in such bad shape that there was no navy to move Hamilcar's troops and family, so they traversed Northern Africa by land caravan towards the Pillars of Heracles and then crossed the Strait of Gibraltar. Hannibal was still a child.

A quote from Wikipedia:

"According to Polybius, Hannibal much later said that when he came upon his father and begged to go with him, Hamilcar agreed and demanded that Hannibal swear that he would never be a friend of Rome as long as he lived. There is even an account of him at a very young age (9 years old) begging his father to take him to an overseas war. In the story, Hannibal's father took him up and brought him to a sacrificial chamber. Hamilcar held Hannibal over the fire roaring in the chamber and made him swear that he would never be a friend of Rome. Other sources report that Hannibal told his father, "I swear so soon as age will permit...I will use fire and steel to arrest the destiny of Rome." According to the tradition, Hannibal's oath took place in the town of Peñíscola, today part of the Valencian Community, Spain."

This is very important to remember. Hannibal swore to his father, as a child, to never be a friend of Rome, and he certainly kept that promise.

Hannibal's military career

There are varying accounts regarding the death of Hamilcar Barca. It is possible he was thrown from his horse and was drowned in a river during battle; that seems to be the most popular theory. Let's just say he died in battle somewhere in Iberia, exact location unknown. Again, any possible records were destroyed or scattered by the Romans.

Upon his death, leadership of Carthaginian forces was given to Hannibal's brother-in-law, Hasdrubal The Fair, who was another military leader, politician, a governor in Iberia and the founder of the City of Cartagena, in around 227 BC. Notice the similarity to the name Carthage. Cartagena was originally founded in the Phoenician name Kart-hadasht, meaning "New City".

Hannibal was now 18 years old and served under Hasdrubal as an officer. Hasdrubal pursued a policy of consolidation of Carthaginian interests in Iberia and even made a treaty with Rome that Carthage would not expand north of the Ebro River if Rome agreed not to expand south of it. Hasdrubal also attempted to gain favor with local Iberian tribes through diplomatic means and consolidate Carthaginian power.

Hasdrubal was assassinated in 221 BC, and Hannibal was then proclaimed commander-in-chief by the army and confirmed in that role by the Carthaginian government.

"The Roman scholar Livy gives a depiction of the young Carthaginian: "No sooner had he arrived...the old soldiers fancied they saw Hamilcar in his youth given back to them; the same bright look; the same fire in his eye, the same trick of countenance and features. Never was one and the same spirit more skillful to meet opposition, to obey, or to command."

After Hannibal assumed command, he spent the next two years consolidating his holdings and completed the conquest of Iberia south of the Ebro. In 220 BC, Hannibal led other conquests in neighboring territories and won the first of his many battles. However, word of this got back to Rome, who was getting nervous regarding Hannibal's growing strength. In response, Rome made an alliance with the City of Saguntum, which lay a considerable distance south of the Ebro. Hannibal not only considered this a breach of the then-existing treaty, but was already planning an attack on Rome, and this was a way to start the war. Hannibal then laid siege to Saguntum, and the city fell after eight months. Hannibal sent the spoils of this conflict to Carthage, gaining him considerable favor amongst the Carthaginian government. However, Rome wanted an explanation as to whether Hannibal had destroyed Saguntum under orders from Carthage. Carthage responded with legal arguments observing the lack of ratification by either government for the treaty to have been violated. The delegation's leader, Fabius Maximus, demanded Carthage choose between peace and war, to which Carthage replied: That's your choice. Fabius chose war.

The Second Punic War

Hannibal departed Cartegena, Spain in late spring of 218 BC. Hannibal fought his way through the tribes of the foothills of the Pyrenees Mountains with clever tactics and stubborn fighting. He then left behind a detachment of 20,000 men to garrison the newly-conquered territories, and then released another 11,000 Iberian troops who showed reluctance to leave their homeland. He then proceeded into the mountains with 40,000 foot soldiers and 12,000 horsemen, along with about 38 battle elephants!

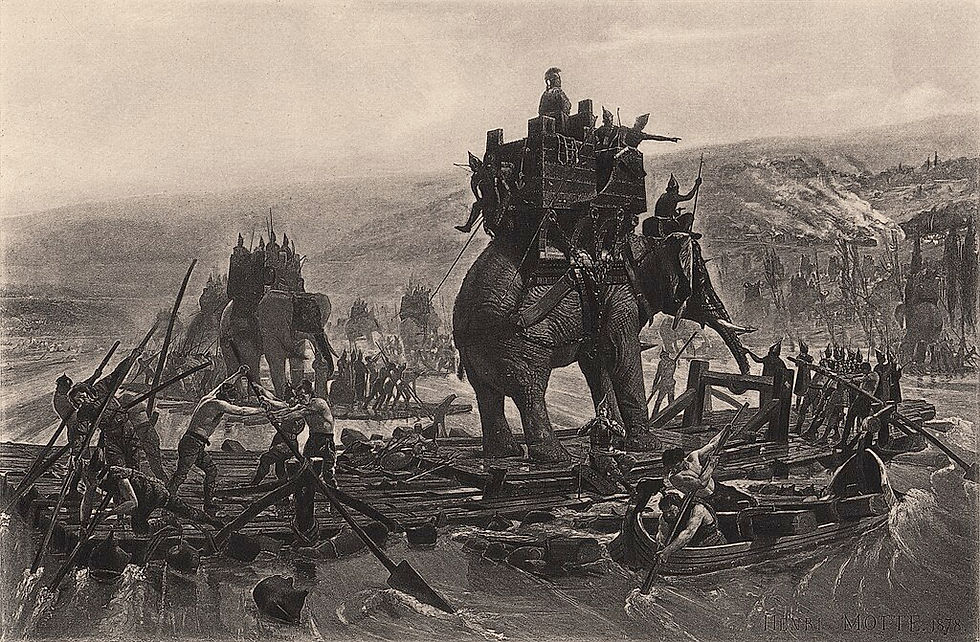

Hannibal realized he had a tough journey ahead. He not only had to fight the natural elements of a mountain crossing with a large number of men, but local tribes such as the Gauls had to be dealt with along the way. Many Gauls eventually even decided to join forces with Hannibal, as they, too, disliked Roman rule. Each challenge along the way was met, but with extreme difficulty. The terrain was very hazardous, and thing like large sheets of ice had to be dealt with in order for the troops and elephants to cross these mountains. Hannibal had perhaps half of his troops remaining and only a few of the elephants when he reached the Rhone. But Hannibal was able to cross the Pyrenees and reach the Rhone River by September 218 BC without the Romans being able to bar his advance. Hannibal was able to outwit the locals trying to stop his advance, then evaded Roman forces by turning inland up the Rhone Valley as opposed to going up the coast. His exact route is still debated by scholars today. Then he had to cross the Rhone. As the North African elephants were not big enough to cross on their own, they had to be rafted across the river. There were still the Alps to cross.

The goal of all this strategic maneuvering was to open a front against the Romans from the north, attacking and subduing colonies and city states along the way, as opposed to a direct attack on Rome itself from the coastline. Hannibal had learned a lot of strategy from his father, Hamilcar, when he was younger, and all of this paid off on this famous journey, which had actually been partially conceptualized by Hamilcar. This invasion would shake up the balance of power in the Mediterranean for two decades. Hannibal was able to evade fighting the Romans along the way and brought the battles to their homeland, much to the dismay of the Roman leader and consul at the time, Scipio.

The three major battles

Upon travelling south from northern Italy, Hannibal directed his forces masterfully, both defeating Roman infantry and evading them along the way with careful strategies. Hannibal had caught Scipio by surprise by the tactic of crossing the Alps, and Scipio and his army were still in Iberia when they learned of his presence in Italy. Scipio transported his troops by sea immediately back to Italy, where they encountered Hannibal at the Battle of Ticinus. Hannibal won this battle due to his superior tactics and cavalry. Scipio was injured during the battle, saved only during a rescue by his son, and retreated back across the Trebia River, where the next major battle would take place.

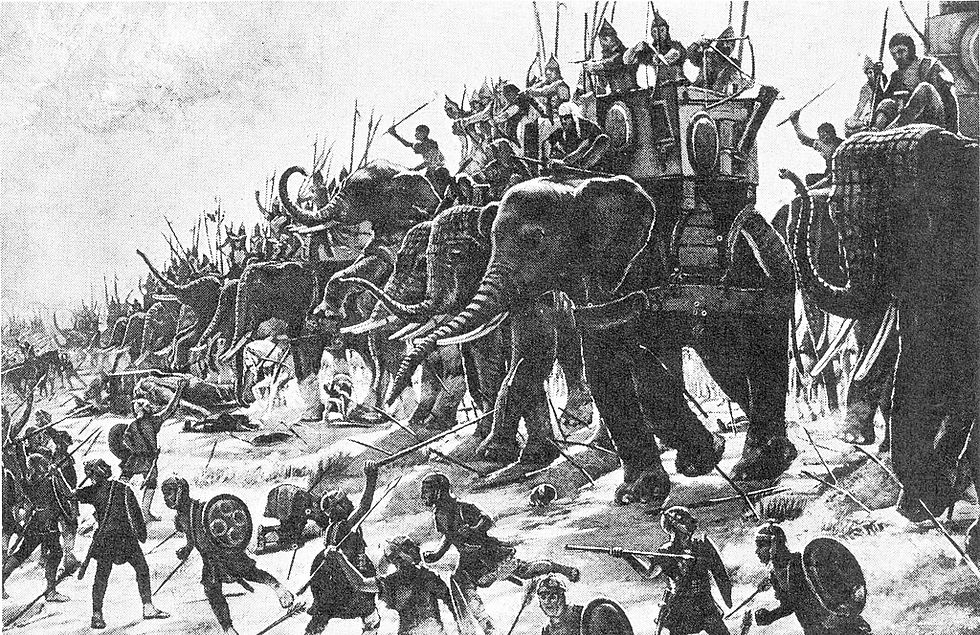

Before the news of the defeat at Ticinus had reached Rome, a second army was sent to the region led by Consul Sempronius. At the Battle of Trebia Hannibal had the chance to show his battlefield mastery once again, where, after wearing down the Roman infantry, he cut it to pieces with a surprise attack and flanking maneuver, devastating the Roman forces. Unfortunately for Hannibal, however, he lost mostly all of his battle elephants in this battle, and they were not used in the next two battles at all, except for the elephant he, himself, rode upon. Throughout history, these battle tactics and maneuvering have become famous and are still studied in military academies today. Hannibal had gained the reputation as a great tactician.

Hannibal quartered his troops then for the winter amongst the Gauls, whose support for Hannibal at that point was fading rapidly. Hannibal used various-colored wigs and disguises to avoid any assassination attempts, and then moved his troops further south in Italy in the spring of 217 BC. The Romans had set themselves up in a defensive posture along both the east and west coasts of Italy, leaving Hannibal the only choice of going through the swamps of central Italy. This was, again, a difficult passage for Hannibal and his troops, and the crossing wiped out a large number of Hannibal's forces.

The Romans had sent a consul named Flaminius to protect this territory of the lower Arno River at the base of these swamplands. However, Flaminius remained encamped at Arretium, and Hannibal outflanked the camp and was able to cut off Flaminius from Rome, forcing a Roman retreat to the shores of Lake Trasimene. There Hannibal destroyed the army of Flaminius, killing Flaminius, as well. This was a very costly lost for Rome and now cleared the path for Hannibal to proceed directly to Rome. However, Hannibal realized he was not prepared to attack Rome itself, having no siege engines or a sufficient amount of manpower to capture such a city. He then opted to exploit his victory by entering central Italy and encouraging a revolt against the major Roman powers.

The Romans then appointed Fabius Maximus as the new dictator. Fabius at that point departed from the Roman tradition of direct confrontation, avoiding open confrontation but still placing his armies in proximity to Hannibal's forces in order to watch his movements. Hannibal conducted several raids, but was unable to lure Fabius into a full-scale battle.

In the spring of 216 BC Hannibal then took the initiative and captured the Roman supply depot at Cannae, cutting of Roman supply routes. In response, Rome appointed two new consuls and built an army of unprecedented size, up to 50- to 80,000 men. Hannibal was able to capitalize on the eagerness of the new Roman army to take him out, and drew them into an entrapment tactic. As a result, the Roman army was fully encircled, leaving no route of escape. Through superior maneuvering, Hannibal was then able to completely wipe out all but a small number of the Roman forces, even with his smaller number of forces.

After Cannae, Rome avoided any more direct confrontations with Hannibal and began to wage a war of attrition, relying on advantages of supply lines and sheer number of forces. Hannibal fought no more battles in Italy after Cannae. It is believe that his refusal to bring the war to Rome was a consequence of lack of commitment from Carthage and the lack of men, money and siege equipment. As a result of Hannibal's victory at Cannae, however, there were many consequences for Rome, and many parts of Italy joined Hannibal's cause as they despised Roman rule. Hannibal forged an alliance with the new tyrant of Syracuse, the Greek city states in Sicily were induced to revolt against Roman control, and the King of Macedonia pledged his support of Hannibal, initiating the First Macedonian War against Rome.

In the long run, the war in Italy settled into a strategic stalemate. I quote:

"Hannibal started the war without the full backing of Carthaginian oligarchy. His attack of Saguntum had presented the oligarchy with a choice of war with Rome or loss of prestige in Iberia. The oligarchy, not Hannibal, controlled the strategic resources of Carthage. Hannibal constantly sought reinforcements from either Iberia or North Africa. Hannibal's troops who were lost in combat were replaced with less well-trained and motivated mercenaries from Italy or Gaul. The commercial interests of the Carthaginian oligarchy dictated the reinforcement and supply of Iberia rather than Hannibal throughout the campaign."

Hannibal retreats

In March 212 BC, after this continued war of attrition, Hannibal captured a coastal city of Tarentum in a surprise attack. Hannibal fought and won several smaller battles during the next five years, eventually making his way to Apulia, where he decided to wait for a reunion with the forces of his brother Hasdrubal. Upon hearing of his brother's death, he then decided to further retire to Calabria, where he maintained himself for another number of years. His brother's head had been cut off, carried across Italy and then tossed over the walls of Hannibal's camp as a cold reminder of the will of the Roman Republic.

In 203 BC, Hannibal's conquest of Italy came to an end after nearly 15 years of fighting. With the military capabilities of Carthage declining, Hannibal was recalled to Carthage to direct the forces of his native country against the already ongoing invasion of Scipio Africanus, son of Scipio.

Battle of Zama

In 202 BC, Scipio Africanus and Hannibal met in a peace conference, but peace was not to be had; the conference was a failure for Carthage. A treaty was drawn up that would have allowed Carthage to keep its African holdings, but they would lose all of the overseas empire, and reparations had to be paid to Rome. At this point, Carthage made a fatal blunder. It's long-aggravated citizens had captured a stranded Roman fleet in the Gulf of Tunis, burned it and plundered it, an action that aggravated the faltering negotiations. Fortified by their newly-acquired supplies, the Carthaginians rejected the proposed treaty, the consequence of which was the Battle of Zama.

The Roman army and Hannibal's Carthaginian forces met outside of Carthage in a place called Zama. The Roman army had been bolstered through a new alliance with a Numidian king who had switched sides and betrayed his previous alliance with Carthage. The Roman army won an early victory by defeating the Carthaginian cavalry decisively and limiting the effectiveness of Carthaginian battle elephants due to their previous experiences. At one point, it seems that Hannibal rallied to a near victory, but Scipio Africanus led a devastating counterattack by assaulting Hannibal's rear. With their foremost general defeated, Carthage decided it had no choice but to surrender. Hannibal was now 46 years old at the conclusion of the war in 201 BC.

A career change and exile

No longer being able to wage war, Hannibal turned to the role of becoming a statesman. He was then elected chief magistrate of the Carthaginian State. Carthage was now forced to pay Rome an indemnity of 10,000 talents. Hannibal then conducted an audit and determined that Carthage had sufficient funds to pay the indemnity without increasing taxation, and Carthage began to rebuild.

Seven years after the Battle of Zama, Rome again became alarmed at the now growing prosperity of Carthage, believing that Hannibal had formed an alliance with Antiochus III of the Seleucid Empire of what is now modern-day Syria. Aware that he had many enemies, including local ones, due to his crackdown on corruption, as well as Rome, Hannibal in 195 BC fled into voluntary exile, first to Tyre, then to Antioch, before finally reaching Ephesus. Hannibal met up there with Antiochus and began discussing war strategies for the Seleucids to possibly use against Rome, who was at war with practically everybody at this point.

War did break out between Rome and the Seleucids, and after several defeats, Antiochus gave Hannibal his first military role since Zama. Hannibal was tasked with building a naval fleet from scratch. Many naval battles occurred in which Hannibal suffered losses. A truce was called in 189 BC, but it included a demand by Rome for Antiochus to hand over Hannibal to their custody. When Hannibal caught wind of these events, he again fled, this time to Crete, but then quickly returned to Anatolia and created an alliance with Prusias I of Bithynia, who was an enemy to a friend of Rome. It gets complicated here. Hannibal won a few battles, both naval and by land, for Prusias by 184 BC. One naval battle was won when Hannibal threw barrels of venomous snakes onto an enemy ship! At this stage, Rome again intervened and demanded that Prusias hand over Hannibal. Prusias agreed, but was determined not to himself fall into enemy hands.

The exact year and cause of the death of Hannibal are unknown. He laid low and avoided capture by Rome. Some say he injured his own finger by drawing his sword, which led to a systemic infection that resulted in his death. Others say that Hannibal poisoned himself to ensure that he would never be captured by Rome. Others believe that it was Prusias who poisoned Hannibal.

Whichever was the case, I quote here:

Before dying, Hannibal is said to have left behind a letter declaring, "Let us relieve the Romans from the anxiety they have so long experienced, since they think it tries their patience too much to wait for an old man's death"."

Varying records and accounts by historians place Hannibal's death anywhere between 183 and 181 BC. But Hannibal's legend lived on. Hannibal caused such distress to the Roman Republic that, whenever disaster threatened thereafter, they used the phrase "Hannibal ad portas", meaning "Hannibal is at the gates", a phrase still used today in modern languages to emphasize the gravity of an emergency.

Now to talk about the music

Whew! That was a lot to unpack. But just as the stories and history of Hannibal were epic, along with the battles he fought, the strategies he created and his mastery of war tactics, I felt that the music for this track had to be just as epic, and there was no easy way out of this. This is a 9:34 track, it's long, the longest track on the album, and it's complicated, just like the story of Hannibal. So here we go.

The very first sound you hear in this track is a sword being drawn from its scabbard. This is to signify battle. Almost all of Hannibal's life was spent in battle.

Due to Hannibal's extensive use of elephants in battle, I tipped my hat off to that fact in the introduction to this track. If you've been listening closely to the tracks, you'll recognize the opening chord progression in the introduction is identical to the opening chord progression of Track 8, Battle Elephants, only here it's half-time and it's in the key of A minor as opposed to the B major of Battle Elephants. The minor key and slower tempo make it seem more ominous, more intense, more dramatic. It's a short intro, but sets the mood and says what it needs to say, that something serious is about to happen.

At :31 we enter Section 1 proper. Due to the story that Hannibal went to his father at the age of nine to ask to be taken to a foreign war, I started this section off in an odd meter of 9/8. Because why not? The bass, rhythm guitars and drums are all syncopated all over this 9/8 meter, giving an almost uneasy feeling of tension. Snare drums hits are all off how you would normally subdivide a 9/8 sequence, for the dramatic effect it provokes. Over all of this is a somewhat not-really melodic synthesizer pattern playing steady 8th notes. This is where the indication of the meter really lies, subdividing the 9/8 into subgroups of 3. If you can count to nine fast enough, go for it, but it's easier to count in threes. On the second pass of this pattern at :51 enters two lead guitars playing in harmony, which helps to lead us into the bridge. Behind this you can also hear a horn playing with some severe pitch bends, mimicking the sound of elephants trumpeting. This whole section is meant to signify Hannibal's first battles on the Iberian peninsula, with all the chaotic sounds of war.

At 1:04 comes the bridge and the introduction of a secondary main theme which also comes back later in the track in a different form. I like doing that so much! The meter switches to 6/8 here, and actually feels like a traditional 6/8 or two measures of three. The strong melodic theme here is played by the same synth, but in unison with the lead guitar. The chord progression is:

a-7, d-7, Bb, E7

F+7, C+7, d-7 to my favorite G#dim7, to lead us back to A minor.

The Bb (Major II) chord here is the odd guy out. I love the tension it brings and the contrast with the two minor chords before it, and it gives a tritone resolution to the E7, which brings some mystery, intrigue and dramatic flare. There's still a lot of syncopation going on in the drums/bass, but the key to the meter here again is the melody. Don't follow the rhythm section or you'll get lost!

At 1:30 there's a repeat of the beginning of Section 1, same thing, but the horn elephants calls are present again, only this time they're clearer because the lead guitars aren't playing. This gives the impression of the elephants charging into battle and getting closer to you.

At 1:50 we go into a bit of a transition section, and we'll call this Section 2, just for identification. Slow, half-time, heavy, and we're now in 4/4. Here is introduced the main piano theme that recurs over and over in different places in this track and is the basis for the final build-out section at the end of the track. But there's only a tease of this pattern for now, it goes twice through this heavy riff, and we're back to 9/8. The riff goes a-7, d-7, F, E7, with some passing notes added in.

We're now starting Section 3 at 2:37. You hear a bass with some flanger effect playing steady 8th notes again under a chord progression in the pad synth. If this bass part sounds familiar, well, good on you! It's actually the exact synth part from Section 1 transposed down a few octaves. The chords in the pad are:

a, a, a, d-7

Db+7, Db+7, Db+7, E+5/-7. And I'll tip my hat to my wife, Cat Corelli, for some help with those chords and the idea for this section.

This chord progression repeats four times in the section. The first two passes, there's no drums, and it's kind of amorphous and intentionally ambiguous. On the second pass a lead guitar starts, gently. On the third pass the drums and rhythm guitars come in and the section gains form and format clearly to give the listener something more relatable. This section reflects Hannibal's journey over the Pyrenees and Alps to begin the war against Rome in northern Italy. It climbs, it rises, it falls, it struggles over rough terrain. On the fourth pass the drums go into a straight 8th note kick drum pattern and the guitars pick it up a notch. The lead continues to build us up into the next section.

At 3:41 we enter, abruptly, Section 4, and a heavy 4/4 riff. The first pass at the riff is unison guitars and bass, the second pass had a crazy lead over top of the riff. The third pass features a unison blast beat riff on the same chords with the kick drums, bass and guitars playing 1/16 note triplets.

Each phrase ends with a big slide onto the root note. This section represents the victory of Hannibal in the Battle of Trebia and the Romans falling.

You can probably tell by now I'm not a big fan of the Roman Republic. Yep, not at all. I've learned to despise them.

Now at 4:29 we enter another transition section, introducing a new piano theme. Or is it? Nope, got ya again. This is the main theme from Section 2 of Battle Elephants, the bass part is even the same, but again, transposed to A, one of many references to that or other album tracks in the last three songs of this album. I like to revisit these themes from other songs earlier in the album for cohesion of the story, both musically and historically. We'll call this Section 5 then.

After the Battle Elephants Section 2 theme reprise, we'll go through that same chord chain, but altered a bit, a few more times. The first pass has a piano solo, the second pass has a violin solo, then the third pass has a guitar solo. This section represents a lull in the fighting in northern Italy as Hannibal changes strategies after losing his elephants in the Battle of Trebia and goes about recruiting the local Gauls to join in the fight. Because we're going back into battle right now.

At 5:41 we begin the Battle of Lake Trasimene section, Section 6. In this track, the sections that are the heaviest all represent Hannibal's three major battle for which he is most famously remembered today. So we're back to a very heavy 4/4 riff with a synth solo over it, then a guitar solo over the next repeat.

We transition here to the Battle of Cannae section, Section 7, so another heavy riff, more guitar soloing. Here we're still in 4/4 but it's half-time, heavy war drums going on and generally a chaotic section once again.

At 6:49 we jump right into Section 8, which is going to be a repeat of that Section 1 9/8 section, only it starts with guitar, bass and the drums are going off wildly in the first pass. The second pass settles into the rhythm, no lead synth this time, and no elephants; the elephants were lost in the Battle of Trebia; remember? The third pass does bring back the harmony lead guitars, but now the drums are playing in a 2/4 against 9/8 meter feeling to really confuse the hell out of my drummer friends. This effect really makes it feel like this section is moving along now.

And then Section 9, which is actually a reprise of the bridge of Section 1, but it's way slowed down, half half-time, in 6/8. But the 6/8 feeling remains in the rhythm guitars playing the 16th notes, so it's a 6 straight time over 6 half time in the rhythm section. Yeah, I love to mix meters, shift downbeats and create uneasy feelings of tension. In this section, like in the original bridge in Section 1, the lead synth and lead guitar are playing that same melody in unison.

Then we're a 8:42 and into the closing section with a reprise of our main piano theme from Section 2 once again. It's a quiet transitional start to this section, which builds into the whole ensemble playing this theme from Section 2, only now the lead guitar is doubling the piano, the guitars are heavy and we're going to ride this out to the end of the track. The first pass is half-time, with the second pass being straight time.

It ends on four piano notes, being once again a fragment of the main theme from Section 2 of Battle Elephants. We've now told the whole story of Hannibal up until the time he gets recalled to defend Carthage against Scipio Africanus at the battle of Zama. We cannot tell the rest of his story yet in this track, because chronologically, album-wise, it just happened yet. We'll get there in Track 9, Third Punic War, and Track 10, Fall of Carthage. But these three tracks really work as a unit to tell the story.

Conclusion

This was quite the ride. I know, it's a long blog, but the story needs to be told. We tend to forget where we come from and how we got here, and I cannot tell the story of the Phoenicians without delving deeply into the exploits of one of their most famous heroes, Hannibal. Remember, Hannibal ad portas, Hannibal is at the gates. Never forget it. There is so much history in this region, but history seems to forget the Phoenicians, even though they gave us so much. The Greeks and those nasty Romans get all the attention and the glory. Never forget the Phoenicians. I never will.

Comments